Minneapolis Can't Get Up

Examining the case for calling the city's fall a controlled demolition

In late May of 2020, protests following the death of George Floyd turned to riots, resulting in the burning of Minneapolis’ 3rd Precinct, with personnel stationed there ordered to abandon their posts before rioters set it ablaze. In all, more than a thousand properties were damaged, with 35 families displaced and one man killed in his business as it burned. City officials estimated in 2020 that it will take a decade to rebuild from the second-most-expensive riots in U.S. history, behind the 1992 Los Angeles riots after the beating of Rodney King. Three and a half years on, violent crime plagues the city: just take a look at a social media profile for Crime Watch Mpls. (I speak from some experience, as the target last year of an attempted mugging during which I recognized my assailant, then unmasked him and told him to fuck off.)

Between that unfortunate death of yesteryear and the condition of the city today, The Fall of Minneapolis (2023) goes some way toward explaining the link. Based on Liz Collin’s They’re Lying: The Media, The Left, and The Death of George Floyd (2022), the documentary—which appeared online the day before Thanksgiving: the same day of my attempted mugging, in fact—exposes gaps in the prevailing narrative surrounding George Floyd’s death, the trial of Derek Chauvin, and the fallout that the city of Minneapolis has suffered ever since.

Returning customers of Radio Free Pizza may recall how I referred last year (in a dispatch dated 1 Oct) to Chauvin’s trial in connection to moral theory, and described Floyd’s death then as a “murder in police custody.” True aficionados will also know that, in my first appearance on The Hrvoje Morić Show, I said (at ~2:57–4:17 in the clip),

I did see it reported recently on Tucker Carlson’s Twitter show [in an episode dated 20 Oct] that apparently the coroner in the death of George Floyd had determined that strangulation and asphyxiation were not potential causes of death, which if that is true, and I haven’t seen this documentation, [then] it seems like then Derek Chauvin, the policeman who was convicted of murder, should not have been convicted of murder.

You might be surprised at how much real-life pushback I received for that simple if-then statement. (In absolute terms, not very much, but relative to the statement itself? You’d think I murdered someone.) But little more than a month later, The Fall of Minneapolis appeared online to make its own case that Chauvin’s 2021 conviction for murder represented a miscarriage of justice.

Featuring more than a dozen interviews with the people directly involved—including exclusive interviews with Chauvin and fellow former officer Alexander Kueng speaking from prison, their families speaking publicly for the first time, along with current and former Minneapolis police officers who tell their harrowing stories from during and after the riots—the film recounts the coordinated surrender of Minneapolis’ 3rd Precinct, reveals the alleged perjury in Chauvin’s trial, and explains why so many officers departed the police force in the aftermath.

Certainly The Fall of Minneapolis presents a critical view of George Floyd’s death and its aftermath, and raises questions about the prevailing narrative of Derek Chauvin’s trial with its allegations of perjury. Considering those allegations in reference to the connection previously made between Chauvin’s trial and the theory of dyadic morality—in which violating a norm is one of a moral transgression’s primary attributes—it’s conceivable to me that public opinion of his guilt (and, therefore, that of the jurors) hinged on whether the restraint techniques that he employed were indeed taught in Minneapolis police training. Accordingly, I believe that alleged perjury carries significant rhetorical weight.

Challenging an accepted (and legally enshrined) narrative, the documentary has enjoyed a contentious reception: though on 11 December the state’s Attorney General Keith Ellison said, “I have not seen [the film],” he opines nonetheless that, “it’s not factually based … I think that it is partisan propaganda.”

He has some cause for suspecting so, of course: Collin is the wife of a former local police union president, and director JC Chaix’s Ph.D. in strategic media for a dissertation on “how neo-Pythagorean mathematical/textual correlations were used to create intersemiotic complementarity in the composition of The Revelation in The King James Bible (1611)”… well, there’s nothing explicitly partisan about that, it’s just an unusual expertise, especially for someone analyzing the mass media today.

But on the opposite side, just the title alone of economist Glenn Loury’s December 2023 “Derek Chauvin Did Not Murder George Floyd” leaves few guessing what Loury’s opinion is now on the outcome of Chauvin’s 2021 trial.

In that dispatch, Loury discusses the concept of “poetic truth” in the context of the Derek Chauvin trial, drawing parallels with the Michael Brown case. Here, Loury defines it as a distorted narrative used to gain power, often thriving through coercion rather than reason. He argues that the belief that Chauvin murdered George Floyd is a poetic truth and not a factual reality. Accordingly, Loury expresses concern about the societal impact of such narratives, leading to unrest, false convictions, and the implementation of race-based policies, and criticizes the potential long-term consequences of accepting these poetic truths as historical facts and of suppressing alternative viewpoints.

The accompanying clip (excerpted from an episode of The Glenn Show) gives us Loury and linguist John McWhorther discussing The Fall of Minneapolis and the questions about the George Floyd case and the trial of Derek Chauvin, scrutinizing the details of the case, including Floyd’s physical condition, drug use, and the circumstances leading to his death, in a manner that challenges the prevailing narrative. After viewing the documentary’s curated body cam footage, which challenges the widely accepted narrative explaining Floyd’s death, Loury and McWorther agree with its thesis that Chauvin did not receive a fair trial.

McWhorter emphasizes the importance of the clear and detailed body cam footage appearing in the documentary, which has led him to question the established facts and to express his concerns that truth may not matter in the aftermath of the case. As he puts it (at ~3:48), “Once again, we’ve been lied to, and the sad thing is, Glenn, nobody left-of-center is going to admit that any of this could be valid. Truth will not matter on this one.” From there, the pair’s discussion touches on previous cases where initial perceptions were challenged, highlighting the potential impact of false narratives on public opinion and policy decisions, as well as the societal consequences of suppressing alternative viewpoints.

A few weeks later, Loury and McWhorter further explored the death of George Floyd—and its consequences—in a conversation with Collin and director JC Chaix, relevant clips from which appear here and here.

In the first clip, the four discuss the trial of Derek Chauvin and question the testimony provided by Chief Medaria Arradondo and Inspector Katie Blackwell, focusing on the alleged perjury surrounding the use of the MRT technique and how the omissions in their testimony that may have influenced the trial’s narrative.

Their conversation shifts to the response from the aforementioned AG Ellison, whose written response disputes Loury’s assertion that Chauvin, Alexander Keung, and Thomas Lane did not cause George Floyd’s death. In response, Chaix points to the autopsy report, arguing that it does not use the term “homicide” and questions the reliability of the prosecution’s claims. With reference to Dr. Martin Tobin’s testimony in the trial, Chaix emphasizes the need for a more comprehensive examination of the entire encounter.

Additionally, McWhorter introduces the idea, that when Floyd repeated, “I can’t breathe,” it might have been a tactic (an example of Floyd “running game”), considering past cases such as that of Eric Garner, after which time such phrases became tropes. Here, their discussion underscores the importance of examining the complete context of the encounter and raises doubts about the prosecution’s narrative in the Chauvin trial.

In our second clip, the four discuss the emotional trauma of former and current Minneapolis police officers as public servants ordered to sacrifice their city’s 3rd Precinct to avoid bloodshed. In the film, officers describe feeling uncared for after they fled the burning precinct, and criticize the lack of riot control gear or arrests for days before its surrender. In the months afterward, the resignation of over 300 officers left the city with a police force reduced by almost 50%.

Meanwhile, as Collin and Chaix recount, the city council doubled down on anti-police rhetoric and paying out massive settlements during an exponential increase in previously-unheard-of crimes like carjackings. Altogether, they argue, Minneapolis’ political leadership has abdicated responsibility and left its constituents feeling unprotected—for which businesses and citizens have begun suing the city—and they express a bleak outlook for restoring safety and hope in the city.

None of this, of course, should be taken as an attempt to whitewash the issue of police brutality, or Chauvin’s own record: as Lee Camp’s Dangerous Ideas reported at the end of last year, the former officer had a long history of excessive force complaints—22 complaints, in fact, resulting in just one disciplinary action. For years police neglected to release footage of Chauvin’s prior assaults—and even of Floyd’s death—and Camp reveals (at ~4:59–5:05) that, with regard to the laws allowing police departments to withhold and heavily redact such footage, “three of the four legislators who wrote the final language had long been police officers themselves.”

(That, I think, makes it all the more curious that the curated body-camera footage in The Fall of Minneapolis should now be changing minds like Loury’s and McWhorter’s. Did the city throw Chauvin under the bus, as Collin and Chaix allege?)

For his part, Chauvin maintains in his communications from prison—where (as discussed in my last appearance on The Hrvoje Morić Show [at ~15:20–16:46]), he was nearly stabbed to death four days after the U.S. supreme court rejected his appeal—that he never intended to kill Floyd. A separate motion from Chauvin for a judge to vacate his guilty plea on a civil-rights charge (for ineffective defense counsel) remains under consideration.

Others in Minneapolis point to additional factors beyond a shrunken police force explaining the city’s crime wave. In the view offered on the “About” page for Crime Watch Mpls, Minnesota’s criminal justice system emphasizes leniency over public safety, evident in practices such as plea bargains, stayed sentences, and probation for a range of crimes. The state’s Criminal History Score calculation and concurrent sentencing policy allow repeat offenders to continue criminal activities with delayed consideration of imprisonment. While the state’s sentencing laws aim for consistent punishments, they reserve prison space for the most violent offenders, resulting in felons serving less time than in most states, even for severe crimes. Requiring offenders to serve only two-thirds of their sentence in prison contributes to Minnesota having a notably short average incarceration length. Flaws extend beyond judges to legislative decisions, the appointed Sentencing Guidelines Commission, and elected officials like mayors and county attorneys, collectively fostering a system that appears to prioritize offender leniency over public safety. The adoption of low or zero-dollar bail requirements further reinforces this lenient approach.

Local judges and prosecutors have become targets of further criticism: for example, Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty, whom AG Ellison removed from a high-profile murder case for being perceived as too lenient on crime. Moriarty, who ran with the endorsement of the local Democratic party, secured her position in the 2022 election with a campaign that raised $294,000. While most of her donors were from Minnesota, she received numerous out-of-state contributions during the campaign’s peak, including many maximum individual donations of $1,000. External independent expenditures supporting Moriarty amounted to an additional $294,000, with liberal groups like TakeAction Minnesota and Faith in Minnesota contributing significantly.

Of course, such groups raise concerns about the influence of dark money and out-of-state donors in Moriarty’s election. Others, too will, warn us that it’s something to worry about in elections across the country, given the predilections of billionaire financier and political donor George Soros, who “gambled that he could swing district attorney elections by heavily funding candidates who favored his version of justice, which focuses on de-prosecution and decarceration in the name of racial equity,” writes Thomas Hogan for City Journal, the urban policy magazine published by the conservative Manhattan Institute think tank (which also sponsors The Glenn Show), in an article dating to last July. “Prosecutors like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, Kim Foxx in Chicago, George Gascón in Los Angeles, and Alvin Bragg in New York rode Soros’ funding to victory”—and to that list we can add MN AG Ellison.

There’s at least circumstantial evidence linking Soros’ legal philosophy and political agenda to rising rates of urban crime. “Soros’ publicly stated premise was that the de-prosecution and decarceration reforms ushered in by his prosecutors would not degrade but in fact improve safety in American cities,” Hogan writes. However:

In poor cities, homicides have spiked, including the largest single-year increase in American history in 2020, continued escalation in 2021, and lingering high rates of murder clustered in cities with progressive prosecutors even after the end of Covid restrictions. (Apologists who blame Covid for homicide increases should note that murders were rising in cities with progressive prosecutors before the pandemic hit.) […] Cities under the influence of Soros-backed prosecutors are less safe than a decade ago. The promise of increased safety was an illusion.

In Hogan’s telling, Soros’ premise that these reforms would enhance safety and benefit minorities has proven to be a miscalculation. Instead, rising crime rates, particularly in homicides, and negative consequences for minority communities have challenged the effectiveness of Soros-backed prosecutors. Moreover, the longevity of these prosecutors in office has been limited, with several facing defeat, resignations, or removals. In his view, Soros’ financial investment in reshaping the American criminal justice system has yielded a mixed and uncertain legacy due to the unforeseen consequences of his interventions.

Many might argue with Hogan: after all, The New York Times reported little more than a week ago that, in 2023, violent crime nationwide was near its lowest levels in 50 years. I suppose that, in response, Hogan might contend that areas without Soros-backed prosecutors are just that much safer. All I can tell you for sure is that last year was the first time anyone here tried to mug me.

Given the additional factors of state sentencing guidelines and the social engineering aims of the donors supporting progressive prosecutors across the country, I’d say that Collin and Chaix have good cause for their bleak assessment of Minneapolis’ prospects. Of course, the coincidence between the city’s crime wave in the years since Floyd’s death and Chauvin’s trial, and the lenient policies of progressive liberal prosecutors, lies beyond the scope of the documentary.

But suspicions of conspiracy have long surrounded both the 2020 riots and Soros’ political donations, and in these narratives, such coincidences find something in the way of a hypothesized explanation. On 29 May, just days after Floyd’s death, a protester in Texas shared video expressing his suspicions that nearby bricks were intentionally left as “a set-up,” though the Trump White House soon blamed their presence on “professional anarchists.” One example of these might have been the so-called Umbrella Man, initially accused of inciting the riot at a local auto parts store in Minneapolis, and who was supposedly identified by police in Summer 2020 but whose identity was later reported as still being sought by the FBI in 2022. That same summer, Rudy Giuliani called Soros “intent on destroying our government” for his donations to the Black Lives Matter movement, which supported the protests.

We see here that conspiracy theories surrounding the 2020 riots emerged among both progressive liberals and conservative nationalists. This, I think, recalls the idea of “poetic truth” to which Loury referred earlier while discussing the distorted narrative of Floyd’s death: both sides invented a conspiratorial narrative composed of whatever explanatory elements their own biases would emphasize.

Interestingly, Catherine Austin Fitts, former U.S. Assistant Secretary for Housing—whose work in this area I mentioned when I first appeared on The Hrvoje Morić Show (at ~6:50–7:34 in the clip)—arrived at her own such theory while looking at the 2020 riots in terms of real estate.

The clip provided here describes how her analysis suggests potential ulterior motives around real estate acquisition in the low-income areas that the riots devastated. That analysis initially mapped locations against political affiliation and pandemic deaths. But she noticed that the locations of damaged buildings aligned suspiciously well with Federal Reserve branches and “opportunity zones” for tax shelters prompted her further investigation.

As Fitts explains, damaged small businesses—often minority-owned—couldn’t reopen without the capital for repairs, after pandemic-related restrictions had already strained them financially. (The capital for repairs might have been hard to come by: of the $500 million in damage done to a five-mile stretch of Minneapolis, more than 60% of it was uninsured.)

With insurance inadequate and repairs unaffordable, properties become cheap to acquire after riots. Big Tech billionaires and other capitalists cashing out stocks could shelter their gains by investing in these distressed areas, acquiring cheap land on which to build out “smart city” infrastructure around Federal Reserve branches—an example of “disaster capitalism” that deliberately undermines small businesses and enables large investors to cheaply acquire properties.

Makes sense to me. I mean, maybe I’m just paranoia, but still, it would make sense to me: as a Minneapolis native who was then and now a resident, I can say from experience that a conspiratorial suspicion prevailed in the city even before the riots transpired. Though I told Hrvoje in my first interview (at ~5:13–6:07 in the clip), “I honestly had a great time. It was seriously like summer camp,” one of the major reasons I said so also gave me the firsthand experience with local paranoia.

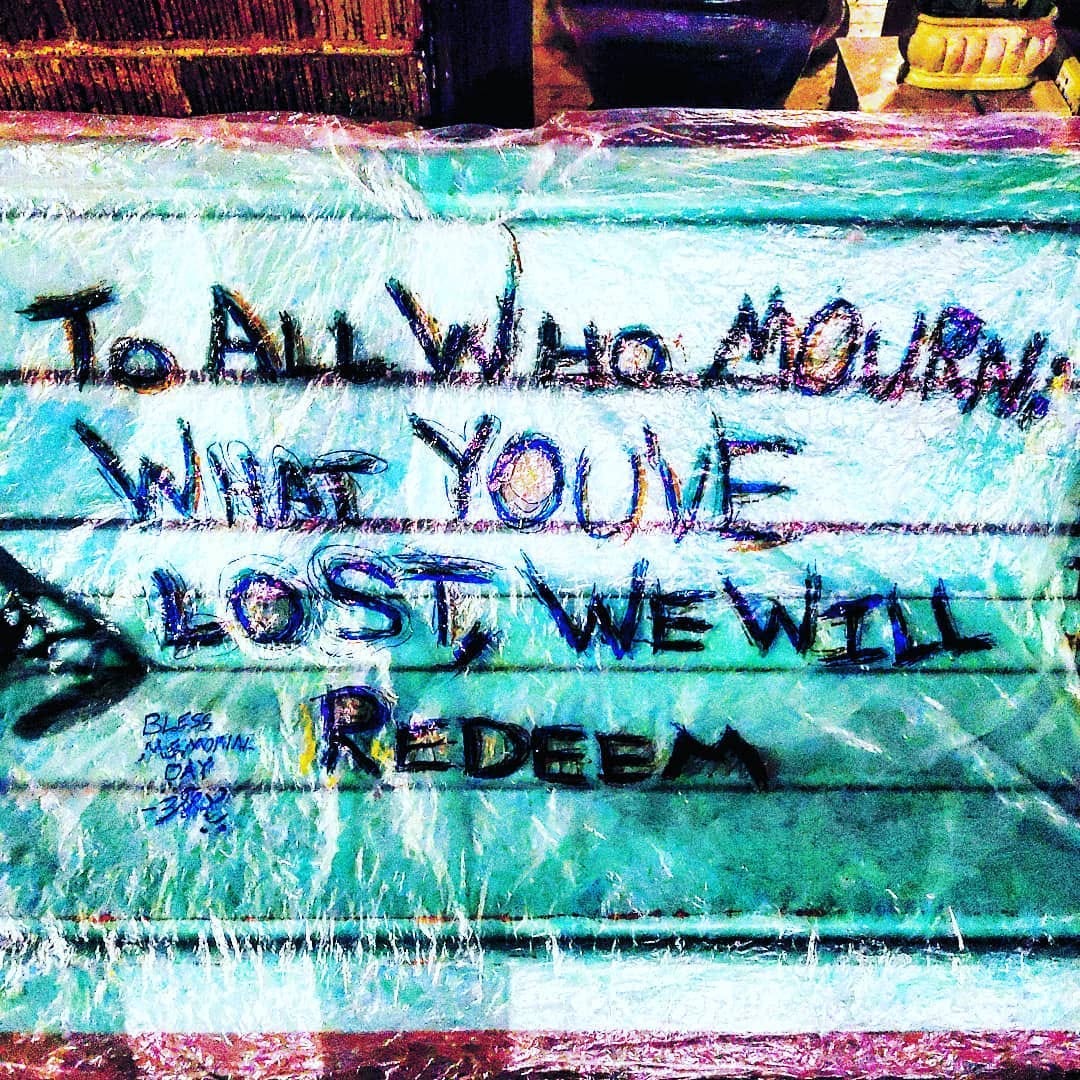

On Monday, 25 May 2020, Memorial Day—the night of Floyd’s death—I visited for a short time with a local beggar whose grift is claiming that he’s an artist and asking people to sign his shirt (or some other object or article of clothing) for him to include in his next gallery showing before he tells them, “…and if you’ve got a couple of bucks, it’ll keep me going.” Though I don’t believe I gave him any money, I did sign what looks to have been a clear plastic raincoat and uploaded a photo of it to Instagram on what has now become the official account of Radio Free Pizza:

“To all who mourn: what you’ve lost, we will redeem,” I wrote (“bless Memorial Day”), consciously mimicking Sherman Alexei but not knowing that, at roughly the same time about four miles away, George Floyd was either soon to die or very recently dead.

Over the course of the week, the viral video of Floyd’s death inspired protests that turned to unrest that turned to riots. I recall that Thursday—the day after the Umbrella Man had smashed the windows at the auto parts store, as mentioned above—my neighbors from the Minneapolis block where I then lived had gathered at dusk in the parking lot beneath my bedroom window to organize a group I affectionately dubbed “the Blockheads.”

As an example of the conspiratorial suspicions I mentioned, a former candidate for city council warned the Blockheads quite earnestly to beware any cars with out-of-state license plates. That caused something of a stir with my roommate at the time, whose own car had been licensed with out-of-state plates and who, therefore, took issue with any protocol that prejudiced him or anyone else with such flimsy cause.

These warnings, however, proved warranted: that fall, a Texas man was charged in federal court (and plead guilty in 2021) with crossing state lines to participate in a riot after driving to Minneapolis—where he fired 13 rifle rounds into the surrendered 3rd Precinct—as one of the Boogaloo Bois, “‘the national network’” that, despite diverse political beliefs, developed around intuited forecasts of widespread unrest and the collapse of civil society in the U.S., which was then “‘going off.’” Of the 17 people charged in federal court with crimes related to arson or riots, only one other—curiously, an apparent Trump supporter from Illinois who sincerely protested Floyd’s death in opposition to law enforcement—hailed from outside the state.

Throughout that night and the next, the Blockheads and I stood watch over the gas station across the street from where, earlier that week, I had crafted a banner out of a raincoat. These nights, I suppose, were the reason I told Hrvoje that the riots were “like summer camp”: we didn’t light a campfire, of course, but nonetheless, I spent those nights among friends and under the stars. Though I don’t believe summer camps for children involve preventing roaming bands of looters from lighting fire to a gas station, or seeing one of your neighbors stand in front of a car and slap a hockey stick against the pavement (though I understand he played racquetball) while shouting, “Warriors, come out to pla-a-ay…!” before the car sped forward, taking him off his feet and knocking him to the ground.

The same day that the 3rd Precinct burned, Governor Walz deployed the state’s National Guard—a little late, I guess—and the day after, Mayor Frey imposed an 8 p.m. curfew for city residents. But May is the finest month of the year in Minneapolis, in my experience as a native, and I wasn’t inclined to remain indoors, choosing instead to enjoy a night on the town and, meanwhile, to share videos with friends on social media which, seeing them now, risk inducing me to cringe. Here’s one from that Friday:

I was joking at the time I recorded that, but I honestly don’t remember: where did I get that fireman’s jacket? For me, the curiosity of its appearance in the videos I’ve kept from that week exemplifies how, as I told Hrvoje, “I just kind of let myself go with the flow, and the flow in that case was complete and total chaos.”

However, in the perspectives of Collin and Chaix’s The Fall of Minneapolis, of Loury and McWhorter after watching their documentary, of Fitts following her analysis of property locations damaged in the riots, and of the Blockheads’ city council candidate in 2020, it seems more appropriate to call it a controlled chaos. “Controlled,” of course, in varying degrees, by different suspected actors, and with diverse possible intents:

For Collin and Chaix, in the decisions of leadership not to equip police with riot gear in the days before the burning of the 3rd Precinct and in the order to surrender it, which functioned as an official invitation to chaos that city officials have perpetuated with anti-police rhetoric;

For Loury and McWhorter, in the media’s distorted presentation of George Floyd’s death for the sensationalist appeal of “poetic truth,” generating outrage through disingenuous reporting;

For Fitts, in the riots’ local economic impact on a city with regional importance to the U.S. financial industry, suggesting an investment opportunity for “disaster capitalism” and, therefore, inspiring her suspicions about whether such an opportunity might have been engineered;

For the Blockheads, in the actions of violent outsiders traveling to Minneapolis from different states to take advantage of civil unrest as a cover for causing physical destruction.

I guess everyone gets a little paranoid sometimes. I guess that’s why last year I saw a man getting thrown out of a bar while shouting, “George Floyd is still alive!”

Of course, no evidence exists (as far as I can tell) for any formal conspiracy to destroy Minneapolis, either among public servants, media outlets, real estate investors, or extremist networks. But, the tumultuous aftermath of the 2020 riots and the trial of Derek Chauvin encouraged a complex web of intrigues and suspicions to develop among the city’s residents—helped along, undoubtedly, with the demoralizing effects of high crime.

Thinking of these conspiratorial narratives, I’m reminded of one of George Carlin’s many enduring quotes: “You don’t need a formal conspiracy when interests converge.” With this in mind, the controlled chaos might be best considered in terms of whose interests it serves.

But I should say the same about the city’s reconstruction. After all, as Mark Bailey observed in a blog post inspired by my attempted mugging in November, “Desperate people make terrible decisions. And we’re in an era that manufactures desperation. Tent cities are proliferating in urban areas. Street crime is commonplace. All of this is only going to get worse until we fix poverty.”

Indeed, I agree: addressing the bleak outlook for the future felt broadly among the city’s residents demands confronting the precarious economic conditions impoverishing its working class. Accordingly, the city’s long recovery following the George Floyd protests will require Minneapolis to undertake its urban revitalization in a manner that supports small businesses with local ownership to protect the economic resilience of the local community, rather than benefitting a financial oligarchy that, as Fitts’ analysis shows, stood to profit from the riots that cost the city so dearly—whatever someone thinks were their original cause.

That was really well written, and the receipts fit in nicely. What I have always maintained is that until citizens come together nothing can ever change to better their lives. Fitts and George Carlin stated were on to what I believed all along that it was a set up. The city government took advantage of a situation to escalate the riots for financial gain. Thank you for exposing Keith Ellison too for what he is all about. It saddens me that I have lived in Minneapolis for decades because when I travelled around, I don't think any city compared and now, I might as well be living in Detroit.