Last time on Radio Free Pizza, we talked about U.S. imperialism in Latin America as it relates to the history of social engineering. Today, let’s turn our attention to the same geopolitical phenomenon, but this time, in the context of global trade.

You’re familiar, I’m sure, with the Panama Canal: the artificial waterway spanning 65 kilometers (shoreline to shoreline) of the Isthmus of Panama in Central America, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and serving for more than a century now as a vital shortcut for global maritime trade, significantly reducing travel time and costs for ships navigating between the two oceans. For that reason, shipping accounts for a full quarter of Panama’s GDP today, despite recent disruptions to this important source of national income resulting from a persistent drought (which included the driest October on record) that has left more than 100 ships queued and waiting for transit, with one having just this month paid $4 million to skip to the front of the line, and with drought-related changes to the rules for booking a ship’s transit expected to force some vessels to participate in auctions to expedite their passages.

(With the U.S. dollar standing as one of the Republic of Panama’s official currencies, and with the other, the Panamanian balboa, pegged 1:1 with the U.S. dollar, it seems too that the cost of transiting the canal provides a useful prop to the imperial currency’s value in foreign exchange, supplementing that of the petrodollar system.)

But because of shipping’s dominance in Panama’s economy, you might not know yet about its mining industry, in which just the Cobre Panama mine, belonging to First Quantum Minerals, accounts for a staggering 5% of the country’s GDP and more than 2% of the country’s total employment.

All that from “the country’s only active mine”! (Emphasis mine!) Though maybe it’s less amazing alongside the knowledge that the Cobre Panama mine accounts for 1% of the world’s copper output.

Indeed, the Cobre Panama mine seems to have been even more of a coup for First Quantum Minerals over the years. With their original 1997 contract granting them twenty years of unrestricted mining exploitation and tax exemptions in exchange for 2% royalty payment to Panama—after negotiations conducted with neither a bidding process, public input, nor environmental impact studies (which become here economic impact studies too, since the mine competes with the canal for fresh water) and with the contract drafted in part by the country’s former Minister of External Affairs—the company has apparently enjoyed enough success in the venture to negotiate a new contract. After all, the country’s total copper exports reached a value of $2.8 billion in 2022, with $1.13 billion of that imported by China. With 20% of those copper imports used in power generators, electrical transmission, battery storage, solar panel, and electric vehicle industries, it’s no wonder that Jiangxi Copper’s own Canadian subsidiary increased its stake in First Quantum Minerals to 10.8% in 2019—and to 18.5% as of 9 November this year—though four years ago such news had little reason to make the press.

Recently, though, there’s been good reason you might have learned more about Panama’s mines: probably one similar to the reason that Jiangxi Copper saw fit to add to its First Quantum holdings. If so, that’s probably because you’ve heard how Panama City has been embroiled in protests, intensifying since 16 October to include as many as 250,000 people, when President Laurentino Cortizo signed a new long-term contract (“overwhelmingly approved […] by lawmakers” following modifications to a text dating to March) with Minera Panama, launched in 2019 as the Panamanian subsidiary of First Quantum Minerals.

Though critics like economist Felipe Argote fear that the company “will take much more from the country economically that it contributes”—not hard to imagine: while “‘Cobre Panama has made over US$3.5 billion since it started operations in 2019,’” he adds elsewhere, “‘it hasn’t paid a penny on income taxes’” (though Minera Panama claims it paid $567 million to the government since December 2021, when the supreme court’s 2017 ruling of the original contract’s unconstitutionality was finally made public: to my mind, a truly bizarre delay)—nonetheless, Trade and Industry Minister Federico Alfaro argued, “the contract’s final approval will send a positive message to future investors.”

The people of Panama, however, did not receive the message of its approval very positively at all, as the videos embedded here (shot on 30 October by yours truly) will hopefully demonstrate. In fact, they took the streets immediately, with protesters “arguing [the contract] is tainted by corruption and too favorable to the Canadian miner, as well as harmful to the environment.” Local business associations estimate that these demonstrations have resulted in $80 million of daily losses.

In my own gloss on the reporting linked and quoted here, the Republic of Panama attempted to pretend that it had an interest in making concessions to its concerned citizens. On 27 October, President Cortizo banned future mining contracts—whatever that might do about anything, when the subject of the protests is a mine on the scale of the existing Cobre Panama—and, on the 29th, called further for a public referendum in December on the contract’s future, pending the referendum’s legislative approval. Nonetheless, “Panama's main workers' union said its members will keep protesting in the streets until the contract is annulled” and 1 November would see the same lawmakers who at first overwhelmingly approved of the contract now bowing to public pressure in a 63-0 vote to rescind the contract, the second of three such votes required to cancel it. On the 2nd, however, some lawmakers removed the contract’s annulment from proposed legislation. Meanwhile, the referendum remained uncertain. Then, just last week, Panama’s supreme court began hearing arguments for challenging the new contract’s constitutionality, and two days ago the court entered deliberations, though many fear that legislative or judicial reversals “could open the door to international arbitration, according to legal experts.”

Returning Radio Free Pizza customers will surely understand why I presume the Investment Court System and its Investor-State Dispute Settlement regime would preside over said arbitration, and why I hazard to guess they’d treat Panama unkindly. Indeed, under the terms of the Panama-Canada free trade agreement, international arbitration could leave Panama on the hook for the Cobre Panama mine’s fair market value, with existing precedent in prior claims against Pakistan in the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes.

After two weeks of protests and escalating tensions throughout the country—during which one protester died “after being run over […] allegedly by a foreign citizen attempting to cross a roadblock”—Kenneth Franklin Darlington Salas, a 77-year-old retired lawyer and professor with dual American-Panamanian citizenship who worked previously as “a spokesman for Marc Harris, a Panamanian accountant who was jailed for 17 years in 2004 after being convicted of money laundering and tax evasion” and who possessed a previous conviction for unlawful possession of a firearm from the same year as Harris’ sentencing, stopped at a roadblock west of Panama City on 7 November, drew a pistol on two protesters, and murdered them in cold blood. For now, Panamanian courts have placed Darlington in a six-month pretrial detention, though the protests he so much detested look sure to continue, with the president having originally proposed a 17 December referendum, before the nation’s electoral court found that “there are no conditions” (meaning, at minimum, that it would require legislative action to authorize) under which the country might hold a referendum—and so the public appears deprived of its voice, and of representation from those who seem to have auctioned off their country.

Indeed, one wonders if the supreme court’s decision will matter to the protesters, who have won the support of local boats that two weeks ago blockaded the port of Punta Rincon to prevent from docking a ship with supplies destined for Cobre Panama, where protests had already reduced production. If such disruptions continue, one may soon wonder if any domestic political action except for holding a popular referendum can protect the mine’s operations.

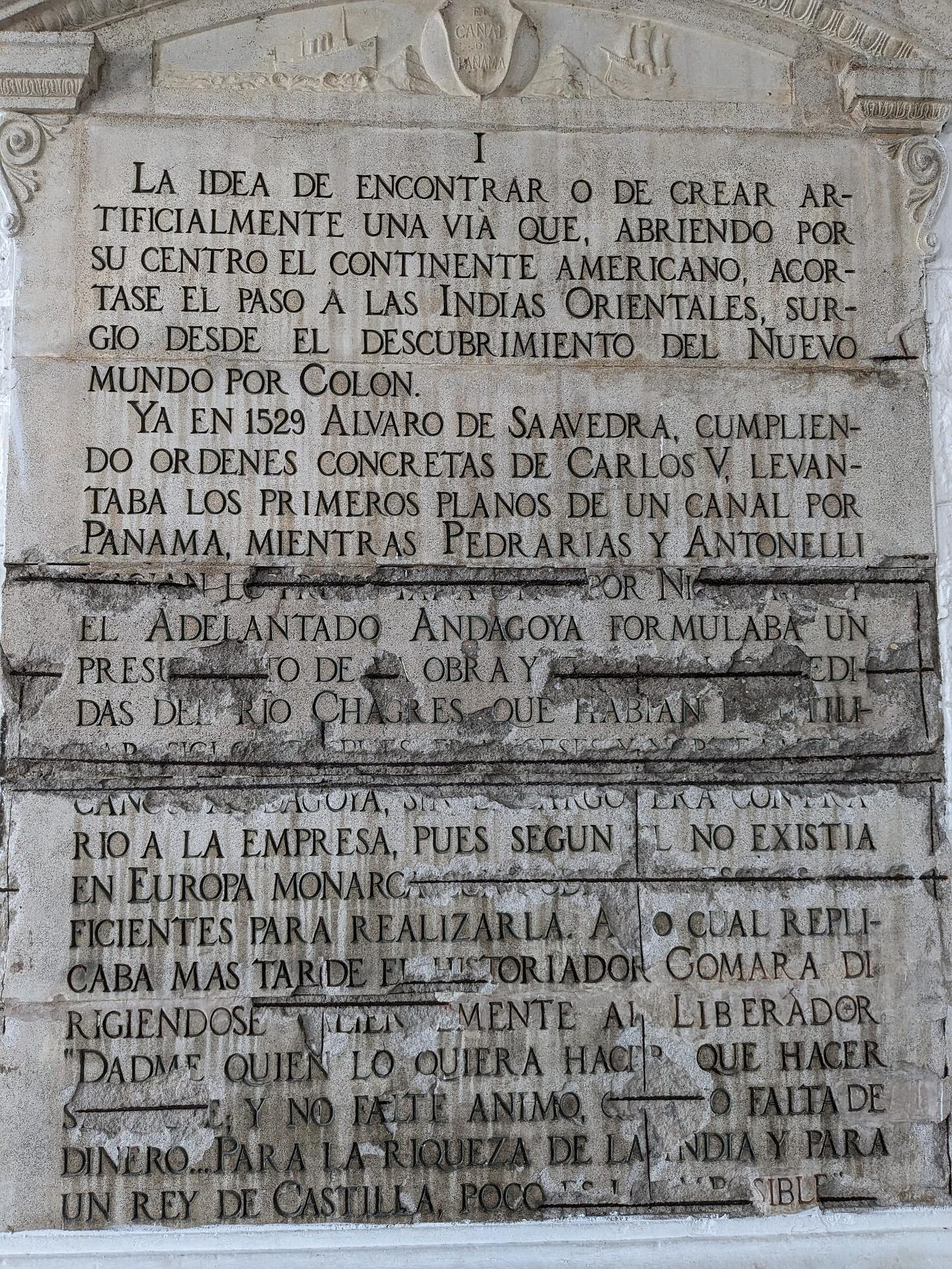

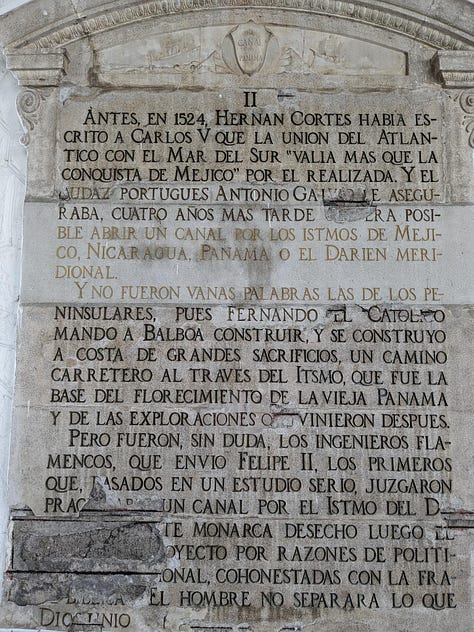

Of course, Panama has been no stranger to the foreign extraction of its native wealth throughout the past half-millennium—only most recently at the hands of First Quantum Minerals—and its people have been therefore long familiar with the violent dimensions of both economics and politics. While the aforementioned canal affords the country its status as a modern focal point for international commerce, the modern Republic of Panama inherits a long history of economic importance that its canal has fantastically amplified. In 1501, the Spanish explorer Rodrigo de Bastidas became the first European to reach Panama’s Caribbean coast, with Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossing the isthmus in 1513. Only sixteen years later, “in 1529 Alvaro de Saavedra […] drew up the first plans for a canal through Panama.”

Sure: why wouldn’t he? Everyone wants to save a little time going back-and-forth from the East Indies. But, of course, for the Spaniards it would remain a distant dream. Still, as part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru until 1717 before its transfer to the Viceroyalty of New Granada (present-day Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela), Panama became a vital part of the Spanish colonial empire as the site where gold from South America was transported to Spain. During this time, Panama City became an important hub for trade and transit.

Certainly, Panama had a pivotal role to play in the Spanish Empire’s extraction of wealth from its colonies. According to Earl J. Hamilton’s “Imports of American Gold and Silver into Spain, 1503–1660” (1929), the records of Casa de Contratación de Sevilla show that Spain extracted at least 181,234 kilograms of gold and 16,632,648 kilograms of silver from all colonies in Americas (before accounting for smuggling), with these extractions helping to inflate the price of goods in Europe sixfold over roughly the same period. With two-thirds of the Spanish imperial profit originating from South America throughout 1581–1660, I estimate that (in USD price per kilogram as of this writing) about $7.27 billion in gold and $8.04 billion in silver passed through Panama on the way to Spain from 1514 (when Pedro Arias Dávila arrived as Royal Governor for Ferdinand II) until 1660.

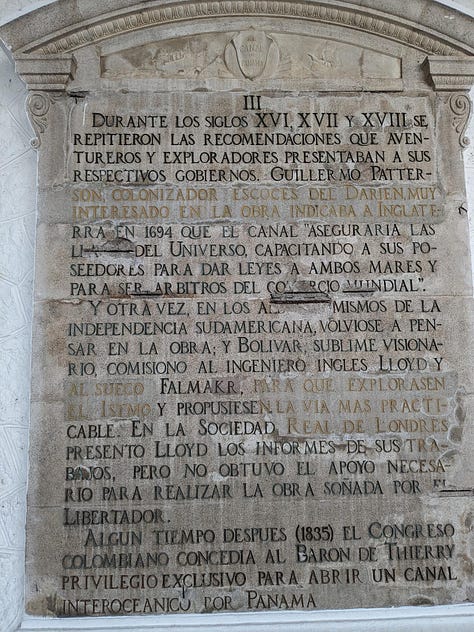

Although Hamilton’s research shows that Spain’s receipts for all specie peaked in 1591–1600, we know nonetheless that the extraction of indigenous wealth from Panama and the surrounding region would continue until 1821, when the empire’s Central American colonies declared independence from Spain and joined the nascent Gran Colombia, led by Simón Bolívar. This union was short-lived, however, and Panama became part of the Republic of New Granada in 1831, which evolved into the United States of Colombia in 1863, and then into the Republic of Colombia in 1886.

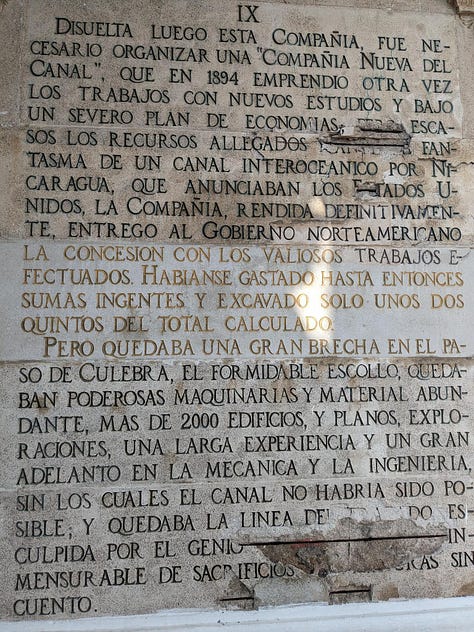

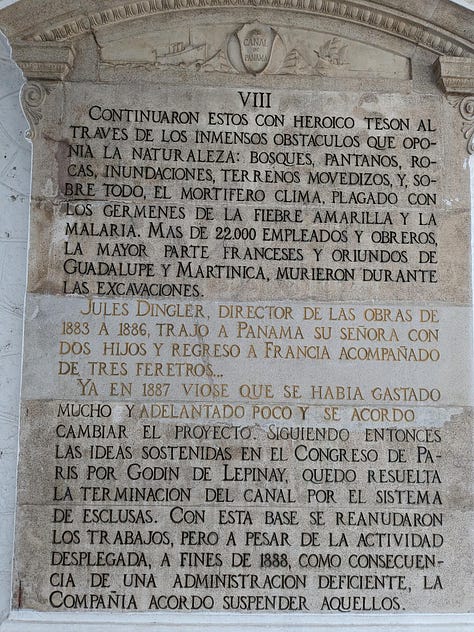

During this time, Panama remained a key commercial hub. The construction of a railroad across the isthmus in the mid-19th century further facilitated trade. (Importantly, a majority of the leaders of Panama’s 1903 secession movement were connected to the Panama Railroad Company, whose aspirations for a nation on the isthmus would put them more closely among the inner circles facilitating the construction of the canal that would supplant their local monopoly.) Meanwhile, international interest developed in constructing a shipping canal across the isthmus, until the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique began work on one in 1881. The ambitious project faced immense engineering challenges and a staggering worker mortality rate, which drove the French company bankrupt in 1889. Nominal work would begin again five years later under another French company, until the United States took control of the project in 1904.

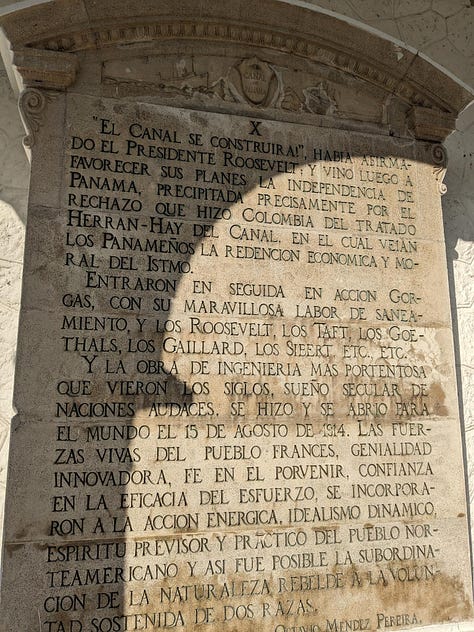

However, the U.S. only took control of the project after arranging Panama’s declaration of independence from Colombia in 1903. As Cathal Nolan explains, the 1898 Spanish-American War had impressed upon the nation the necessity of efficient transit for its interoceanic naval power. The British Empire at first opposed these American interests, but with an expected clash with Germany on the historical horizon, the benefit to their Caribbean possessions of good relations with the Americans inspired the British to lift their objections. With American imperial designs no longer facing opposition from rival empires, then-Secretary of State John Hay signed a treaty with a 100-year lease on the land to build the canal.

But the Colombian senate rejected the treaty. Accordingly, Nolan writes, “Private interests linked to the old French canal company now approached both private Americans and the Roosevelt administration to support the secession of Panama from Colombia, to be quickly followed by signature of a canal treaty.” That secession meant supporting some of the same rebels whose uprisings had six times prior inspired the U.S. to land troops (with permission from Colombia) to protect transit and trade.

Those American interests must have found the French proposal amenable:

In October 1903, the U.S. Navy sent warships to steam off Panama’s coast. On November 2, their captains were ordered to land marines, seize the Panama railroad, and block any Colombian reinforcements […] the revolt began the next day […] Fewer than 1,000 men in a disorganized rebel army […] bribed and threatened local Colombian forces to surrender or leave, thereby securing a nearly bloodless success under the shadow of American naval guns and presidential intent. On November 4, Panama duly declared independence. Bogotá asked for American help to put the rebels down. Instead, Hay extended de facto recognition to the Republic of Panama two days later. De jure recognition followed in a week. On November 18, a canal treaty was signed with the new republic. In it, the United States guaranteed Panama’s independence against Colombian military action, getting bargain terms and a 10-mile-wide canal zone across its new protectorate […] It was not until oil was discovered in Colombia years later, making reconciliation of interest to Washington, that the United States implicitly, but not explicitly, admitted earlier wrongdoing by agreeing to pay symbolic compensation of $25 million.

Panama’s separation from Colombia in 1903 was a pivotal moment. The swiftly negotiated Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty granted the U.S. control over the newly created Panama Canal Zone. Construction thereafter began again in earnest, continuing until they finished it in 1914. During that time, President Theodore Roosevelt popularized the so-called Panama hat (which in fact originate from Ecuador) when he became the first sitting president to leave the U.S. while visiting to witness (and admire the formal expression of U.S. colonial power inherent in) the canal’s construction, about which he would brag in 1911, “I took the Isthmus, started the canal and then left Congress not to debate the canal but to debate me.”

In fact, the canal’s operation was so eagerly awaited that it opened for international commerce in October 1913—with, as Voluntary Society notes, a cost of $375,000,000 to the U.S. Treasury, and in defiance of the fact that administering the Canal Zone “is not a function of the federal government that is authorized under the Constitution.”

However you feel about how the U.S. sliced up Colombia, the daunting obstacles overcome and local governments overthrown to finish the Panama Canal were nothing less than such monumental feats so often seem to require. Completing it represented a watershed moment that fundamentally altered global trade routes and firmly cemented Panama’s position as a crucial crossroads of international commerce.

The 20th century saw that position develop further. In 1965, President Johnson announced U.S. intentions to revise the Panama Canal Treaty to recognize Panamanian sovereignty over the Canal Zone, and in 1977, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties led to the eventual transfer of the Panama Canal from the U.S. to Panama, paving the way for Panama to regain full sovereignty over the canal in 1999 in the supposed culmination of a long journey toward political self-determination and control over the nation’s commercial lifeline.

During that transition, however, the U.S. would launch Operation Just Cause, invading Panama in 1989 to oust General Manuel Antonio Noriega, who—as David Johnston first reported for The New York Times in 1991—received “$322,000 in cash and gifts during his relationship of more than 31 years” with the U.S. Army and Central Intelligence Agency.

“In the Iran-contra affair,” writes Johnston, “documents disclosed that General Noriega offered to conduct sabotage raids inside Nicaragua in support of the Reagan Administration’s efforts to oust the Sandinista government.” In 2009, Bobby Ghosh (reporting for TIME) added further gloss on Noriega’s alleged offers of military support:

Upon taking power, he allowed the U.S. to set up listening posts in Panama and is believed to have served as a conduit for U.S. funds to Nicaraguan contra rebels fighting the leftist Sandinista government. The U.S. looked the other way as Noriega established what would be described as a “narco-kleptocracy,” but the relationship eventually soured and the U.S. invasion of 1989 ended his rule.

But one must wonder if, indeed, the U.S. merely looked the other way. As Seymour Hersh reported in 1986, “One official who said he had extensively reviewed the most sensitive intelligence available to the American Government on General Noriega, including reports from agents and intercepts, described most of the specifics as ‘having to do with gun and drug running.’” With this mind, it’s difficult to imagine that the U.S. intelligence community might simultaneously:

Entertain help from Noriega in fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua;

Facilitate the sale of arms to Iran in defiance of its nation’s own embargo to fund the Contras rebelling against the Sandinistas;

Encourage the Contras to fund themselves through drug trafficking;

and yet have been itself uninvolved in Noriega’s own participation in the drug trade that funded their Contras.

Regardless, however, of the CIA’s official knowledge and potential involvement, congressional funding passed for the Contras in 1986, and seems to have dimmed the agency’s interest in helping the Contras to fund themselves in the drug trade. Coincidentally or not, American affections for Noriega turned sour in the same period, and—similar in some ways to how the U.S. treated the Republic of Colombia (propping them up in their Panamanian territories when it suited their economic interests, until it could arrange greater profit from knocking the crutches out from under them)—the U.S. soon overthrew its former assets. After first indicting Noriega on violating U.S. federal drug laws in February 1988, the U.S. government grew increasingly confrontational, until December 1989, when four U.S. Marines dressed in civilian clothes and driving a car with Michigan license plates ran a Panamanian military roadblock in front of the Panamanian Defense Forces’ headquarters. Panamanian soldiers fired on their car, killing 1st. Lt. Robert Paz.

Those seeking more on American/Panamanian relations and on Operation Just Cause would do well to consult The Panama Deception, winner of the 1992 Academy Award for Best Documentary, however you can find it. As the narrator tells us (at ~33:40):

The Marines were reported [by The Los Angeles Times] to be part of a group known as the “Hard Chargers,” known for provoking confrontations with PDF forces. The Pentagon claimed the Marines were unarmed and lost, but local witnesses said that they were armed, and [that they] exchanged fire with the PDF headquarters, wounding a soldier and two civilians.

Whether he was armed or not, 1st. Lt. Paz’s death providing the Bush Administration with its final excuse for Operation Just Cause. The U.S. invaded on 20 December 1989, and Noriega surrendered himself into custody two weeks later, for transport to the U.S. for his arraignment.

While the operation achieved its primary objective, it also resulted in a significant number of civilian casualties. The exact number of civilian deaths remains a subject of debate and controversy, with estimates varying widely. From the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, we know that 18,000 civilians remained homeless in October 1993, almost four years after the invasion.

Of course, the 1989 invasion caused significant political and social upheaval in Panama—and not just in 1991, with President Guillermo Endara’s proposed amendment to the Panamanian constitution abolishing the country’s right to an army (and matching U.S. law to renegotiate the Torrijos-Carter Treaties now that Panama had lost any military with which to defend the canal), as The Panama Deception notes at ~12:27:41—and it paved the way for major reforms: Panama has held several democratic elections since the U.S. invasion, and in 1994, the country approved a new constitution to reinforce democratic principles and safeguard human rights.

Meanwhile, Panama has significantly reformed its financial industry, which had since 1970 enjoyed the tax-exempt status granted to international transactions, with regulatory and legislative changes to modernize its financial system—one which already, according to James Corbett (at ~14:59), “was created in 1927 and deliberately, specifically modeled on Delaware’s laws”—with the aim of discouraging drug-traffickers from using Panama for money-laundering, and to enhance the sector’s stability and attractiveness to international investors.

In establishing a favorable environment for offshore finance—with benefits including the establishment of offshore banking and corporate services, and tax benefits including exemptions on certain types of income and transactions—the country has drawn international businesses and investors seeking tax-efficient structures, helped along by Panama’s use of the U.S. dollar as its official currency, providing monetary stability and reducing exchange-rate risk for businesses and investors. Finally, the expansion of the Colón Free Trade Zone (CFTZ)—the largest free trade zone in the Western Hemisphere, within which companies pay 0% tax on profits from foreign operations and on profits from the import and re-export of merchandise—further benefitted Panama’s financial and banking sectors.

Here, the spirit of Noriega’s narco-kleptocracy appears to linger, despite the reforms to the country’s banking sector enacted in the 1990s: as the Financial Action Task Force reported in its “Money Laundering Vulnerabilities of Free Trade Zones“ (2010), numerous businesses in the CFTZ participated in “a massive Colombian/Lebanese drug trafficking and money laundering cell operating globally” which received a cut “of the drug proceeds sold in the Middle East […] to ensure that the traffickers could operate in certain areas” with the CFTZ serving as “a central point of delivery for bulk cash proceeds of drugs.”

Of course, that FATF report only prefigured further revelations about money laundering in Panama. Eight years prior, the arrest for laundering profits from illegal freon trafficking of Marc Harris (for whom worked the 2023 protest shooter Kenneth Darlington, as described above)—not in Panama but in Nicaragua, to where Harris first escaped despite at least a dozen complaints of fraud or theft having been made prior to his flight—had served as a minor prelude to that report. But each only foreshadowed the 2016 disclosure of the Panama Papers.

The scandal of the Panama Papers would come to light when an anonymous source leaked 11.5 million documents from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). These documents, spanning over 40 years, revealed the intricate web of offshore companies, shell corporations, and financial secrecy employed by individuals and entities around the world to hide their wealth and evade taxes, representing one of the most significant and far-reaching scandals related to offshore financial practices and tax evasion in modern history.

The Panama Papers implicated numerous politicians, celebrities, business leaders, and public figures from various countries. Notable names included heads of state, government officials, and high-profile individuals who had used offshore accounts and shell companies to conceal their personal assets. (The ICIJ’s “Panama Papers: The Power Players” interactive page displays fourteen different heads of state on its first screen.) The 2017 assassination via car-bombing of Daphne Anne Caruana Galizia—the Maltese journalist and anti-corruption activist who reported in February 2016 (and whose reporting the Panama Papers’ release two months later would confirm) on then-Minister for Energy and Health Konrad Mizzi and then-chief of staff Keith Schembri having established shell corporations in Panama owned by trusts in New Zealand to hide their assets—and the subsequent resignation (in 2019) of then-Prime Minister Joseph Muscat may underscore the political or industrial importance of those whom the Panama Papers had named.

Curiously absent, as Kelly Phillips Erb wrote in 2016 for Forbes, were American names among those of Mossack Fonseca’s most widely publicized clients. Nonetheless, these included heiress and actress Liesel Pritzker Simmons, billionaire real estate developer Igor Olenicoff (convicted in 2008 for failing to disclose $200 million in offshore accounts), asset manager John Michael “Red” Crim (convicted in 2008 for advising clients to evade taxes using offshore accounts), Pennsylvania businessman Andrew Mogilyansky (who pleaded guilty in 2009 to charges stemming from his flight to Russia to have sex with 13- and 14-year-old orphans), music and film producer David Geffen, finance expert and life coach Marianna Olszewski (who according to the BBC hired a 90-year-old British man to pose as the owner of her offshore company), and former CitiGroup CEO Sanford Weill.

But Erb doesn’t want us to presume the guilt of those named. “Owning an offshore company or creating an offshore trust isn’t illegal. In fact, it’s perfectly legal in most countries, including in the United States”—in fact, Erb tells us as well, “the United States is considered something of a tax haven. Flexible entity structures, corporate tax breaks and tax-favored capital gains can result in a relatively low tax burden, making it an attractive place to do business”—and only becomes criminal when done to evade taxes or to hide assets from creditors.

Altogether, the Panama Papers exposed further the extent to which offshore accounts were exploited to evade taxes, launder money, and engage in illegal financial activities, raising concerns about inequality and global financial transparency. Widespread public outrage prompted governments to take action against tax evasion and money laundering, with some countries initiating investigations and legal proceedings against those named in the leaked documents, while international organizations pushed for greater transparency in financial systems and offshore tax havens. The scandal served as a catalyst for global discussions on the need for stricter financial regulations and efforts to combat illicit financial practices.

I hypothesize, of course, that the U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989 (and the country’s subsequent “collaboration” with the International Monetary Fund) engendered the expansion of its free trade zone and the business-friendly reforms to its finance industry, which led in turn to the offshore banking scandal of the Panama Papers. Certainly though, temporal sequence doesn’t equal direct causation: still, while I’m at it, I’ll add to that hypothesis and suggest that the same neoliberal economic policies go some way toward explaining why Panamanians see political corruption as the country’s most pressing concern.

Regardless of my own suppositions, the potential for scandals in its finance industry to topple governments in other hemispheres gives us only the latest example of the curious habit that Panama’s political history has had—from the early days of the Spanish conquest, and the colony’s subsequent role in facilitating the extraction of wealth from Spanish colonies during the colonial era, to the construction of the Panama Canal, and the further ascendance of the newly formed Republic of Panama’s importance in global trade—of coinciding with profound shifts in geopolitics and the international economy.

After seeing how Panama’s history has been so closely intertwined with economic interests and geopolitical shifts—enough that it changed the country’s very geography—it’s clear that the country’s domestic politics and its position in international trade demand our close attention. The long-term contract signed with (a subsidiary of) First Quantum Minerals from Canada echoes a historical pattern of foreign extraction of Panama’s wealth, and the violence erupting at the hands of foreign citizens at roadblocks echoes too the escalating tensions preceding and the immediate justification provided for the U.S.’s 1989 invasion of Panama. (Meanwhile, U.S. officials have already begun calling to send additional troops to supplement the Security Force Assistance Brigade already operating in the Darien Gap straddling the border of Panama and Colombia.)

With this long history in mind (along with those historical rhymes), the situation in Panama in November 2023 seems quite a lot less unprecedented than the contemporary discourse of “climate change” may make the objects of today’s protests appear. If one starts telling that history with the imperial extraction of precious metals in the 1500s, and continues telling it on through to the realization four hundred years later of the original colonists’ dream of a transoceanic canal at the hands of an entirely different empire—and if one follows the story further still, through its development into a friendly laundromat for intelligence agencies and tax-exempt offshore banking in the decades following the canal’s construction and the concomitant ascent of the country’s importance in international trade logistics—then, upon hearing today’s story of political corruption facilitating the corporate extraction of base metals for the essential components of electric vehicles, one can’t help but think that the country’s history exemplifies the patterns of conquest according to which the capital order has so long operated, regardless of whether the pole of that order has seated its political executive in the Alhambra or in the White House.

Recognizing and articulating these patterns will allow us (we hope!) to deduce the next twists that arise as these and other deep trends of our civilization play out. For now, we’ll see if the country’s legislature passes a bill rescinding the contract, or if democratic processes yield the legislative action necessary to hold a public referendum, or if its highest court cancels the contract before the aforementioned efforts unfold. Even if they do, the country’s liability under international arbitration could range as high as $50 billion: more than three times the government’s annual expenses.

In that case, I’d say, we would then see the same wealth extraction of which Panama has so long been victim, except now through judicial penalty imposed by the international governance institutions serving imperial finance, and acting here as a fallback to ensure Panama remains a vassal to the capital order. But until we learn the court’s decision, we can only hope for the best, and that the people of Panama soon receive better than what they’ve so long endured.